We are proud to feature Rose Fortune as part of our Legacy Coffee Series.

Rose Fortune is one of the most compelling, intriguing figures in Nova Scotian history. Most rumours about her personal history are more conjecture than memory; while some facts exist, details of her private life remain a mystery.

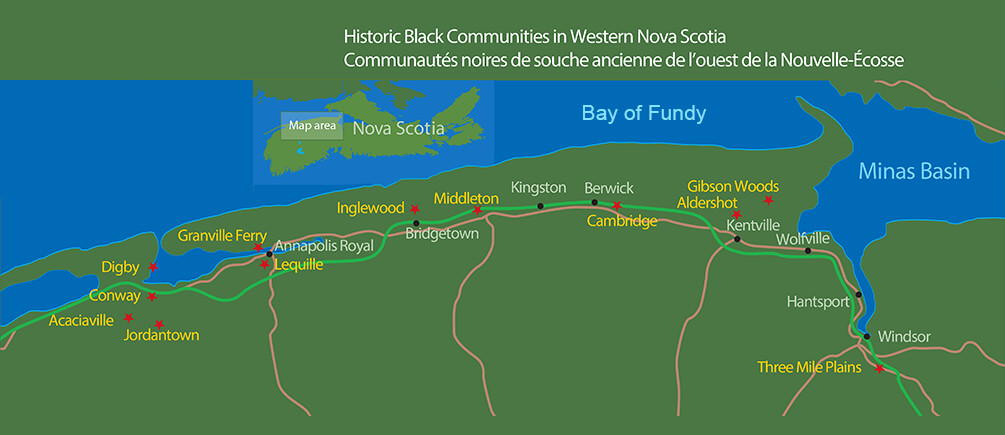

For any era, she was a person of remarkable character. As a self-employed African- descended woman in early-1800s Annapolis Royal, who created and operated a one- person transport company using her wheelbarrow, while moonlighting as self-appointed Port Constable, she must be accorded the status of ‘unique’.

Evidence suggests this singular woman was born March 13, 1774, probably coming to Nova Scotia from Virginia or Maryland, perhaps with the Frederick Davoue family (var. Devoe, Devost, Devone). Based upon a single document, NS Archives & Record Management accepts her as the daughter of a ‘Fortune’ who came to Nova Scotia following the American Revolutionary War. They conclude that the unnamed child (‘Fortune, a free Negro. Family consisting of one man, one woman, and one child over the age of 10’) enumerated on a Loyalist Muster roll of 1784 ‘…almost certainly refer(s) to the family of Rose Fortune’. As yet, no further evidence has been found to confirm or refute this claim.

An impressive person, very authoritative, and clearly a dynamic figure, Rose Fortune lived a full life in Annapolis Royal. She greeted passengers coming ashore and transported their luggage to their destination. Through her indomitable resolve, she managed to keep order on the Annapolis wharf, and became the town’s one-person Police Department.

Judge Haliburton was a regular client, relying upon Rose to waken him mornings after conducting day court, to get him aboard ship in time to sail to Digby to hold court there.

The only known image of Miss Fortune is an anonymous watercolour dated from the 1820s. Some have remarked that her dressing style was somewhat odd. In the watercolour, “her petticoat …shows under her dress, her coat (is) much shorter than her apron, her lace cap, tied under the chin and worn under a straw hat”. She is wearing white gloves or mittens, shoes with pointed toes, heels several inches high and is carrying a straw basket. According to a source on Loyalist dress, these were the fashion for women through the 18th and early 19th century. This source suggests that some Black Loyalists may have been relatively upper class, their clothing reflecting their status from their lives in the Thirteen Colonies, the clothes they had been able to bring with them, and their economic circumstances after arriving in their new homeland.

The 1852 diary of a Colonel Sleigh (departing from a disagreeable lodging house) offers this description: “…I was aided in my hasty efforts to quit the abominable inn, by a curious old Negro woman, rather stunted in growth …and dressed in a man’s coat and felt hat; she had a small stick in her hand which she applied lustily to the backs of all who did not jump instantly out of her way. Poor old dame! She was evidently a privileged

character.” He seems to be referring to Rose Fortune, who would have been nearly 80 at the time. Rose had either one or two daughters, one purportedly an ancestor to the Lewis family of Annapolis Royal. Rose’s grandsons James and Oscar (who later left to work on the railroad) carried on her business, using horse and wagon. Inheriting his grandmother’s strength, James was famed locally for lifting anchors. ‘James Lewis & Son’ had nine horses for general trucking, until James’ son introduced a truck in 1931. ‘Lewis Transfer’ continued operations in Annapolis Royal until the late 20th century.

Records of St. Luke’s Anglican Church in the Parish of Annapolis, County Annapolis state that Rose Fortune of Annapolis was buried in an unmarked grave at the Royal Garrison Cemetery on 20 February 1864 (age listed as ‘unknown supposed about 90’). James J. Ritchie, Rector, performed the ceremony.